An edible color palette

Comments: +

April 21 2011

As designers, we know color is important. But when food is your medium, color can be powerful enough to influence taste—and affect health.

Say hello to Blue No. 1, Yellow No. 5, and Red No. 40.

These numbers make up part of an artificial color palette approved by the United States’ Food and Drug Administration. First introduced in 1906, the FDA’s Pure Food and Drug Act (and later the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act) was put in place to ensure the safety and wholesomeness of food products. Before this, more than eighty dyes were used to color food, without regulation—the same dye could be used to color both clothing and candy.

Currently, the FD&C color palette features seven colors that can be used in the production of food, along with two additional colors for limited use.

In the European Union, a similar system is in place for assessing food additives (both artificial and natural), denoted by E numbers. But for the purpose of this article, we’ll stick to the FD&C numbers.

Artificial dyes have been used to color food for decades, giving us the unnaturally neon food we’ve grown to love. Without them, soft drinks would be clear, Cheetos would be beige, Froot Loops would just be Cheerios, and Easter eggs wouldn’t be nearly as much fun.

While it may not come as a surprise that Cheetos are not naturally dayglo-orange (or naturally anything, for that matter), its color may be more important than we think. As revealed in a recent New York Times article, taste testers at Cornell University’s Food and Brand Lab who sampled a Yellow No. 6-less version of the snack were left feeling unsatisfied.

Their fingers did not turn orange. And their brains did not register much cheese flavor, even though the Cheetos tasted just as they did with food coloring.

“People ranked the taste as bland and said that they weren’t much fun to eat,” says Brian Wansink, a professor at Cornell. Of course, it couldn’t help that naked Cheetos appear as an unappetizing off-white—or as the New York Times describes, “like shriveled larvae of a large insect.”

Besides making our food colorful, these artificial dyes—made up of tar derivatives, long-chain hydrocarbons, and other petrochemicals—have been linked to hyperactivity in children (although the FDA says evidence is inconclusive), and have even been tested to cure spinal injuries in lab rats.

So what exactly are they?

The primary colors

Typical of modern dyes, Blue No. 1 was originally derived from coal tar. Today, most manufacturers produce it synthetically from an oil base. Also known as “Brilliant Blue FCF,” it is used to color products like Gatorade, soft drinks, candy, and mouthwash. Along with Yellow No. 5 and Red No. 40, it is one of the most commonly used colors, and can be combined with Yellow No. 5 to create various shades of green. In 2003, The FDA warned of several reports of toxicity associated with its use, including death.

This royal blue dye is a synthetic version of the plant-based indigo, the same colorant used to dye blue jeans. It can be found in soft drinks, candy such as M&Ms, frozen deserts, breakfast cereals, and bakery products. It is use medical dyes, surgical sutures, and for testing milk. The World Health Organization gives Blue No. 2 a toxicology rating of B: Available data not entirely sufficient to meet requirements acceptable for food use.

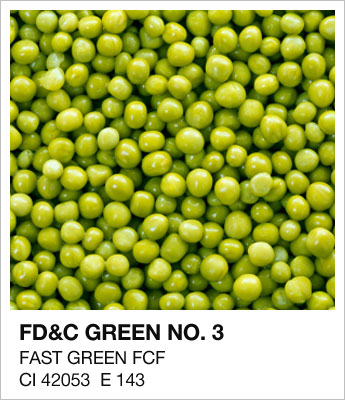

Like many of the other current FD&C colors, Green No. 3 was created as a replacement for another dye that was delisted after health concerns (replacing Green No. 2 in this case). Green No. 3, or “Fast Green FCF,” is used in products like canned peas, candy, fish, and vegetables. The dye is not permitted in the European Union due to animal studies which showed it to be a possible carcinogen.

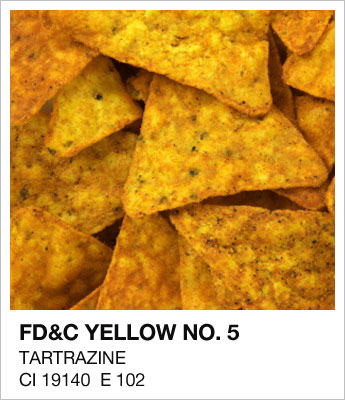

Derived from coal tar, Tartrazine is a lemon yellow azo dye. It is one of the most widely used additives, found in products like Kraft Macaroni and Cheese, Mountain Dew, Doritos, breakfast cereals, candy, chewing gum, jam, pickles, yogurt, vitamins, and prescription drugs. The dye is banned in Norway and the Britain’s Foods Standard Agency has called for a voluntary phase-out of its use in foods due to links to hyperactivity in children.

As the name suggests, Sunset Yellow is a reddish yellow coloring. Like Yellow No. 5, it is derived from coal tar, and its effects on health have been questioned. It is banned in Norway and Finland, and was included in the UK’s push for voluntary phase-out. It can be found in orange soda, hot chocolate mix, breakfast cereal, and candy like Reese’s Pieces.

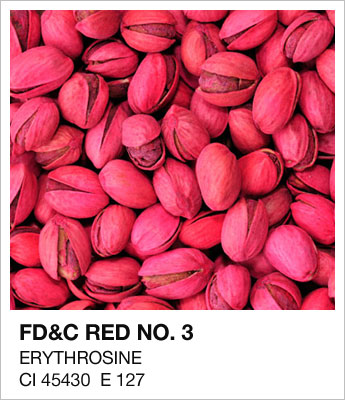

Red No. 3, also known by its chemical name Erythrosine, is a cherry-pink dye used to color products like maraschino cherries, pistachios, canned fruit, candy, popsicles, cake decorating gels, and toothpaste. It is also used in printing inks, as a biological stain, a dental plaque disclosing agent, and in X-rays. In 1990, the U.S. FDA placed a partial ban on Red No. 3 after research showed high doses could cause cancer in rats.

Allura Red is the newest color of the bunch, approved in 1971, and was introduced to replace the banned Red No. 4. Despite the popular misconception, Red No. 40 is not derived from insects (that would be carmine). This azo dye was originally manufactured from coal tar, but is now mostly made from petroleum. It is banned in Denmark, Belgium, France, Switzerland, and Sweden. It was also included in UK’s voluntary phase-out in 2009, due to hyperactivity in children. Red No. 40 can be found in sweets like Twizzlers, soft drinks, condiments, and cosmetics.

Limited use colors

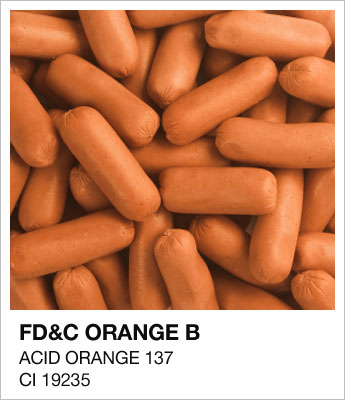

Derived from coal tar, Orange B is limited for use only in hot dog and sausage casings. In 1978, the FDA announced its use could result in exposure to beta-naphthylamine, a known cancer-causing additive. Beta-naphthylamine is listed on the Center for Disease Control’s Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards.

An azo dye approved for use only in coloring citrus peels. The dye is used in Florida to mask color variations with oranges and tangerines throughout the seasons (it is not used in California). According to A Consumer's Dictionary of Food Additives, studies have shown health problems including cancer from heavy ingestion and from exposure to the skin.

According to Gatorade’s website, artificial colors are added to its products to “help in flavor perception and enable you to tell different flavors apart.” They also are quick to point out, “All colors and ingredients in Gatorade qualify for human consumption according to the requirements of the FDA, added at the lowest possible level to achieve the desired color.”

Some grocery stores, including Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s, have put an outright ban on artificially colored foods.

Not all food coloring is as scary as the FD&C color palette, however. Cola gets its color from caramelized sugar (although that’s been recently scrutinized too), cheddar cheese gets its orange color from annatto and paprika, and some modern brands are turning to natural options like turmeric or beets for color.

Other brands have recently decided to do away with color completely in some of their products, including Kraft’s Kool-Aid Invisible and Organic White Cheddar Macaroni and Cheese.

If it wasn’t evident before, food has shown us the power of color goes much beyond what’s visible.

Invisible snack, anyone?

Filed under: culture

Comments