Bringing Bliss to non–speakers

Comments: +

August 17 2010

As a graphic designer, typography is the backbone of my practice. Fascinated with the construction of letterforms, my interest lead me to the work of chemical engineer and Holocaust survivor, Charles K. Bliss, who devoted his life to developing a system of bringing people closer together.

This is the story of an international auxiliary language that brought many people a voice they otherwise would not have.

Born in Austria, Bliss grew up among many nationalities that were constantly in conflict. As World War II broke out in Europe, he left his factory in Vienna and fled to Shanghai in 1940, where there was an international settlement that allowed him to stay and work as a photographer and filmmaker. In the six years that Bliss stayed in China, he became drawn to Chinese ideograms and paid scholars to teach him about the history of the characters. Combining his new observations with his knowledge of mathematics, molecular formulae and electrical pictorials, Bliss decided to develop an international auxiliary language. He envisioned his system of symbols to break down barriers of understanding between people. Once the war was over, Bliss moved to Sydney and began what he believed was his life’s work.

The logic of Blissymbols

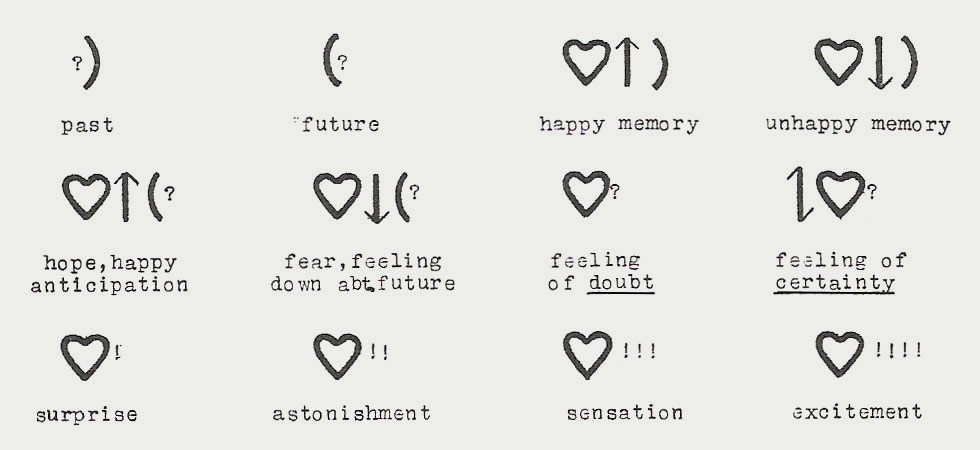

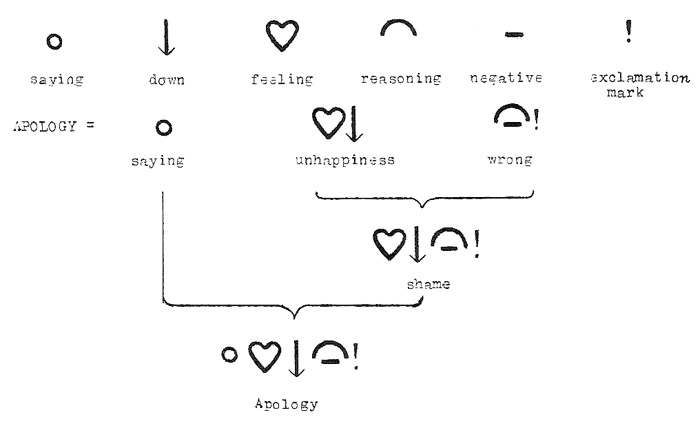

Bliss spent his post-war life designing a system of symbols, as he felt international conflict was caused mostly by long-term misunderstanding and ambiguity. His education in chemical engineering urged him to use concepts that were modular and logical. Beginning with ten simple icons, Bliss devised a way in which they could be arranged to show complex and abstract meanings.

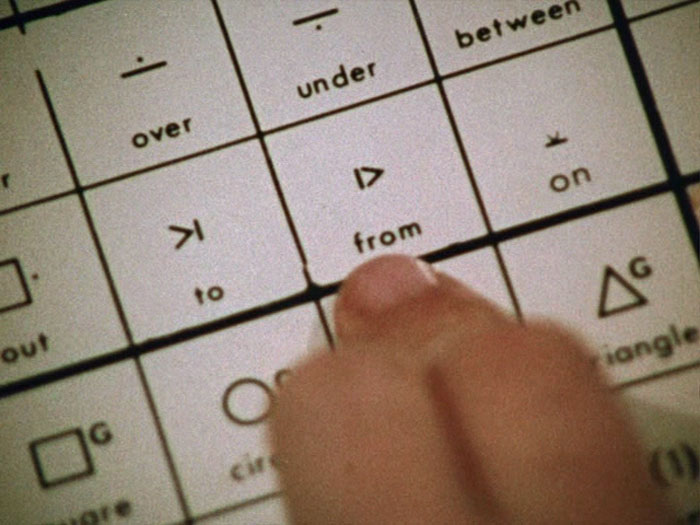

Bliss’ system combined the logic of science, pictographs and graphical symbols such as arrows and hearts in a logical way to form complex meanings. Arbitrary elements such as numbers indicated positioning. For example, a week would be represented by the combination of sun, horizon and 7 to symbolize seven days. Red would be the number 1 with the symbol for color (eye and earth) as red is the first in the sequence of a color spectrum. Other simple ideographic compounds include son, which would be the combination of the symbol for male under a roof, meaning a male protected within a family. Bliss commissioned a commercial draftsman to redraw his symbols so that they were standardized and matched the characters of a typewriter. The symbols were designed to be simple to draw and use.

Symbols in Use

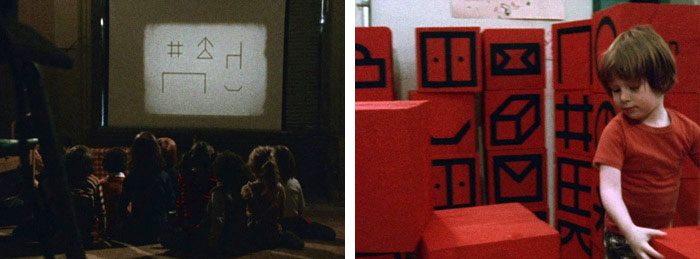

Just as the logic of Bradbury Thompson’s Alphabet 26 helped some early readers with recognizing letterforms, Bliss soon found a niche audience for his system of communication. Initially intended to aid cognitive development and provide a logical approach to early reading, Bliss discovered that his symbols benefitted more than just young children. Blissymbols became a reliable form of communication for patients of cerebral palsy, a condition caused by brain damage that affects the vocal chords and speech. Many children affected by this condition were treated like babies because of their inability to express themselves emotionally, even though their intelligence was not impaired.

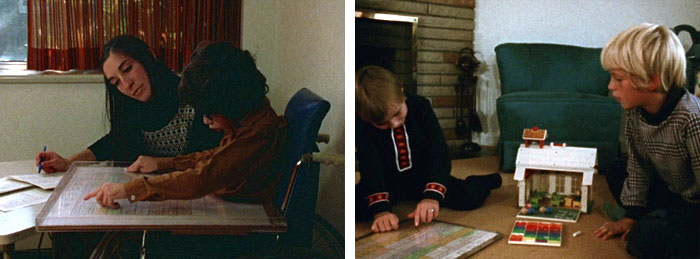

Blissymbolics were first used in 1971, by the Ontario Crippled Children’s Centre in Toronto, Canada, and have since become a popular method of augmentative and alternative communication. The symbols were organized onto a board, with 500 characters within arm’s reach. The board could be attached to a wheelchair, and also had the English words underneath to translate the symbols to other readers. Blissymbols gave handicapped children a chance to speak to others other than their direct family and school instructors.

Although Charles K. Bliss died in 1985, his work became more widely recognized in the mid-80’s after 12-year-old, Rachel Zimmerman invented a Blissymbolic Printer. Traditionally, users pointed to a display board full of symbols and required someone to sit next to them to interpret what they wanted to say. As part of a school science fair, Zimmerman created a software program with a touch pad that translated the symbols tapped on the board onto a computer screen, allowing their communication to be recorded. Zimmerman’s invention allowed non-speaking patients to communicate independently without assistance and also made it possible to write e-mails in different languages.

While many of us are attracted to the large selections of beautifully designed typefaces and new gadgets like the iPad, we tend to forget that others are more limited in their communication. Blissymbols may not be typically recognized or known by the general population but they are being currently used by over ten thousand people with speech impairment including physically handicapped, autistic, aphasic patients and victims of strokes.

As an inventor, Bliss’s work is compared to that of Louis Braille who devised the communication method for the visually impaired, as well as John Logie Baird, the first inventor of the television and broadcast. The language is not flawless, and hardly unifies as many people or nationalities as Bliss originally intended it to, but it does accomplish helping a small group of people interact with others. Amidst today’s ever-changing forms of communication and media, it interesting to study alternative systems such as Blissymbols, to explore visual communication as a means to connect more people.

The majority of research for this article was based on Mr. Symbol Man, produced in 1974 by the National Film Board of Canada and Film Australia. The short documentary records the development of the symbols and is explained by the inventor himself. Further information on Blissymbols can be found through Blissymbolics International, which actively promotes awareness and international usage of the language.

Cheryl Yau is a graphic designer with working experience in Hong Kong and Toronto. In Fall 2010, Cheryl will begin her MFA in Design Criticism at the School of Visual Arts in New York. Visit cherylyau.com and her blog for more work.

Filed under: typography

Comments